SYDNEY, Australia — It was on a recent trip to Indonesia that, as a male bureaucrat sounded forth on a vast span of subjects without being asked to do so, I realized that the English language was in need of a new addition: the manologue. This otherwise perfectly charming man droned on and on, issuing a steady stream of words as I sat cramped in a tiny room with a group of fellow journalists and squinted at the labels on the soda cans hospitably placed on a table in front of us.

Finally, I deciphered the words “HERBAL — TO RELEASE TRAPPED WIND.” After several minutes during which I silently prayed none of my colleagues would reach for a drink, the official at last uttered the words, “Now, to answer your question.”

So why did we get so many words between the question asked and the answer given? Why were they spoken at all? And how can you stem such extraneous, long-winded trains of thought? How can you politely say to a prolix associate, as a TV host might: “We’re almost out of time; can you keep this short?”

Above all, why do so many men do this?

It was not the first time one of us had asked a question about a minor issue during our study tour of the bustling, gridlocked capital Jakarta and been treated to a largely unrelated exposition on an entirely different idea. Our schedule was jammed with politicians, diplomats, ministers and editors from Indonesia and Australia, important men who were used to occupying space, time and attention, and would talk at numbing length. The perfect conditions, in other words, for an epidemic of manologues.

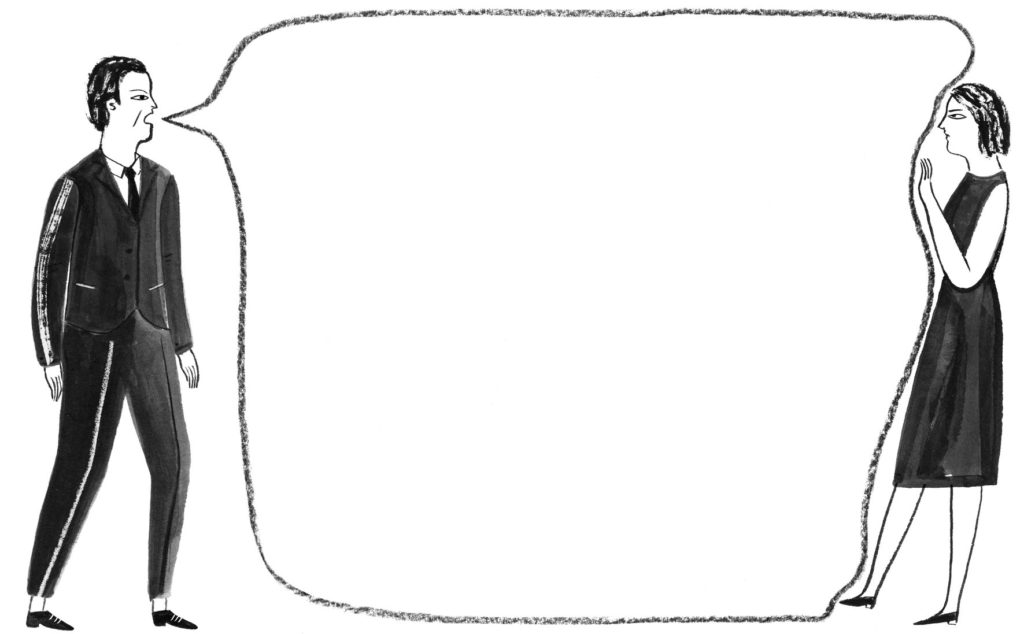

The manologue takes many forms, but is characterized by the proffering of words not asked for, of views not solicited and of arguments unsought. It is underwritten by the doubtful assumption that the audience will naturally be interested, and that this interest will not flag. And that when it comes to speeches or commentary, longer is better.

The prevalence of the manologue is deeply rooted in the fact that men take, and are allocated, more time to talk in almost every professional setting. Women self-censor, edit, apologize for speaking. Men expound.

Of course, some women can be equally long-winded, but it is far less common. The fact that this tendency is masculine has been well established in social science. The larger the group, the more likely men are to speak (unless it is in a social setting like a lunch break). One study, conducted by researchers at Brigham Young University and Princeton, found that when women are outnumbered, they speak for between a quarter and a third less time than the men.

Men also talk more directly; women hedge. They use more phrases like “kind of,” “probably” or “maybe,” as well as more fillers like “um,” “ah” and “I mean.” They also turn sentences into questions, seeking affirmation: “Isn’t it?” Women are interrupted more, by both men and women.

It is also clear that the more powerful men become, the more they speak. This would seem a natural correlation, but the same is not true for women. The reason for this, according to a Yale study, is that women worry about “negative consequences” — that is, a backlash — if they are more voluble. Troublingly, the study found that their fears were well founded, as both male and female listeners were quick to think these women were talking too much, too aggressively. In other words, men are rewarded for speaking, while women are punished.

The problem is global and endemic across all media. Female characters speak less in Disney films today than they used to — even princesses get a minority of the speaking lines in films in which they’re the principal: In the 2013 animated movie “Frozen,” for example, male characters get 59 percent of the lines. A quick search for best monologues in film or movies reveals that they are almost all male. If you took Princess Leia out of “Star Wars,” the total speaking time for female characters is 63 seconds out of the original trilogy’s 386 minutes.

One New Zealand study found that in formal contexts calling for expository speech, like seminars, TV discussions and classroom debates, men talk more often and for longer. Women use words to explore, men to explain.

So here is the conundrum: Including women is not the same as hearing women. As the Princeton and Brigham Young study noted, “having a seat at the table is very different than having a voice.” Women at the table will attest to finding themselves talked over, cut off, interrupted or forced to politely listen to reams of lengthy speeches.

The conditions required for women to speak more are, not surprisingly, that more women are present, and that women are leading. According to a Harvard study, female students spoke more when a female instructor was in the classroom.

One leading Australian current affairs television show, “Q&A,” came up with an obvious yet smart response. After a review found that the program featured a greater number of male panelists, who were asked more questions and spoke longer, the producers promised to publish data documenting not just the show’s gender balance, but accounting for how much time guests spoke.

“We won’t get the voice share perfect straight away,” wrote the show’s producer, Amanda Collinge, “but we are actively trying to improve, and being open about it.”

But if you’re a man who wants to counter your manologue tendency, try this: When you hear yourself saying, “Now, to answer your question,” ask yourself whether there was a good reason you didn’t start at exactly that point. Otherwise, these manologues may never, ever end.