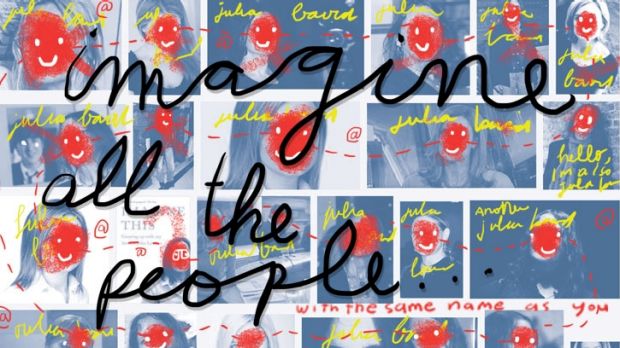

Like many people, I often receive emails in error, intended for someone with the same name as me in a land far away. As John Lennon’s sister’s name is also Julia Baird, I have often been asked to guest DJ on radio stations and review albums, which has been tempting. I also get emails for a Julia Baird in midwest America who clearly plays netball, has a lot of girl’s nights out and recently enrolled at university – go Julia! I usually just write a short email back informing them of the mistaken identity and it stops.

But recently I encountered a Julia Baird who would not give up. First, she forwarded me ads for running shoes. Then she wrote simply saying: “I hope my sync is back!” I wrote back: “Nope”. But I kept getting messages from her saying “test”, “this is a test” and asking “does this work”? And so a conversation began. As it turns out, my new friend Julia Baird was trying to sync her PC with a tablet and just getting the emails all wrong. She is a clinical psychologist from Dallas with two great-grandchildren and is quite a sweetheart. We talked about writing – she wrote a complicated novel about lies but while she enjoyed the process, it was too long to publish. I told her I wrote too.

In between I got more “tests” and photos of burgers and fries. She apologised again for “electronic illiteracy” and said she’d been reading my columns and encouraged me to “keep it up”. She added perceptively: “My guess is that you ‘can’t not write’ as the drive to write is in your heart.”

I began to think more about my Texan friend. Then, as she was now in my automatic address book, I began to make the same mistakes. I sent her by accident a beautiful email I had received from a New York friend about a column I had written on having cancer. I was a bit embarrassed – it was so intimate. But Julia’s next email soon arrived with a gush of kindness. She thanked me for sharing it with her, gave some advice, praised my approach and told me to contact an old friend of hers, a cancer therapist who works to teach people to “nurture the truly important things in life”. She signed off: “I know we are new friends and only because of my poor computer skills but I firmly believe that it was meant to be!”

And so it is, in the middle of ugly terror attacks, rank and feral partisanship, and frequently heartless approaches to people fleeing hell in their homelands, we still so often encounter kindness in strangers. And while we often vilify online relationships as shallow and inferior, the truth is it is possible to be closer to people we have never met than people we see every day.

And it’s not weird at all.

For in the midst of abuse, trolling and utter dickheadery online, we can always find fragments of tenderness. Like my Twitter friends Jane, who is grieving the sudden death of her nephew but still writes to see how I am, and scientist Darren, who is so patently a good and decent man and has often helped with my research.

I have spent several months recovering from a massive cancer-removal operation this year, and during that time was stunned by how quickly the prospect of death erases divisions between us. It’s quite astonishing.

Perhaps it’s the recognition that we are all vulnerable. Perhaps it’s the understanding that the time we all have with each other – not just family and friends, but colleagues and acquaintances and even passers-by – can be more fleeting than we know. When we think this way, and remember a life can be snuffed out in an instant, we are immediately more gentle with each other.

After writing a column about my illness, I was buoyed by the words of strangers.

Victor told me: “Not a day goes by that I don’t think of the fact that I am lucky to be here. Sometimes it can be a guilty feeling. And when things are going really bad, I just stop and think that at least I am alive and healthy. Like you said, family is everything and having them and being here to support and love them is all that matters to me now.”

Jill, who waited five days for cancer surgery, and spent them meditating, and living with “a heightened sense of awareness, a sharpened sense of priorities, and despite adversity, an overwhelming sense of calm”. She writes: “I am still trying to hold onto how beautiful life felt in those five days.”

The stripping back of everything ephemeral and unimportant can put you on a kind of high that is tough to relinquish when you return to normal life. Another friend, Paul, telling me he had kidney cancer a few years ago, said, “in some ways it’s a really wonderful experience. Almost euphoric … it cuts through the clutter and crap in your life and makes you see what’s important, which is friends and family. It’s impossible to hang onto that feeling at 100 per cent intensity – and probably undesirable anyway – but it does stay with you in a good way.”

It has, and it will. As a man called Richard – who is waiting for his own scars to heal – wrote to tell me: “Life is precious. Grab it by the throat.”