Veruca Salt wanted it all. Today, tomorrow and the whole world. Geese who lay gold eggs for Easter. Cream buns and doughnuts, “pink macaroons and a million balloons and performing baboons… a party with rooms full of laugher, ten thousand tons of ice cream.” I know Roald Dahl made a cautionary tale of her, but how excellent does that sound? I want that too.

Still, I would not dream, in 2012, of suggesting that anyone could “have it all.” Just typing those words makes me itch. It is a lame, abused, over-used and now meaningless phrase usually flung at women to suggest they cannot work and be mothers, which is demonstrably ridiculous, or to girls, to tell them to limit their horizons while still growing wings.

No one on the planet has it all; being human means not having it all, growing past the age of, say, two, means accepting that you are not Lord and Mistress of the Universe. Yet the idea of “having it all” – rooted in unrealistic expectations – has somehow been linked to workingwomen. The more women succeed professionally, it seems, the more we talk about their failures; they must be bad mothers, there must be someone, somewhere, suffering for their achievements.

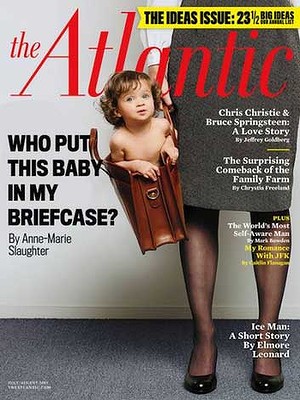

Ever since The Atlantic published a cover story by Anne-Marie Slaughter, the first female director of policy planning for the U.S. State Department, suggesting that “Women Still Can’t Have It All,” newspapers, magazines, blogs and the twitter-sphere across the globe have crackled with anger, sympathy, vitriol, frustration, and recognition. Slaughter commuted weekly to her “dream job” in Washington, and spent weekends with her family in New Jersey; she gave it up after two years. It was not possible, she decided, to mesh “high-level government work with the needs of two teenage boys.”

Advertisement

The piece was lengthy, well researched and beautifully executed. The title may be the most provocative part of it. Slaughter writes clearly about difficulties high-achieving working mothers face – the response alone indicates it remains a scorchingly real issue today. Her suggestions: flexible work practices, prioritizing productivity over face time, redefining the arc of a successful career, and making school schedules match work schedules are all very good.

But it would wrong to draw the conclusion, from the hype accompanying the article, that working is incompatible with mothering.

First, she is writing from a particularly American perspective, a land of no mandated maternity leave, and of an elite work culture characterized by boasts of working long hours, called being “time-macho.” Australians work long hours, but boast of leisure time; we expect women to take six to 12 months maternity leave, and, often, return to work part-time after the birth of a child.

Second, Slaughter returned to Princeton as a professor. This is what she considers scaling down: “I teach a full course load; write regular print and online columns on foreign policy; give 40 to 50 speeches a year; appear regularly on TV and radio; and am working on a new academic book.”

Third, at a time of a global recession and high divorce rates, few women have the luxury to not work. For most, the problem now is not so much working hours, but the precipitous drop in real incomes, the extraordinary gap between rich and poor, the shrinking of the middle class, and extensive layoffs.

Fourth, the idea of “having it all” sets up a straw feminist – a kind of Veruca Salt who supposedly promised women endless pie and ice-cream, and well-oiled working and parenting schedules. I know no feminist who touts this, only those who argue that both fathers and mothers should be entitled to leave and flexibility in their workplaces. This is necessary, and practical, not greedy or deceitful. Yet the headline on the video accompanying Slaughter’s piece read: “Have Feminists Sold Women a Fiction?”

Find me a single feminist who has claimed that women are not torn between competing demands of children and bosses – the cliché is “juggle” – and I will bake you twenty apple pies while balancing my children on my head.

Men are torn too. The most recent studies in the US report in recent years men felt a higher degree of work –life guilt than women. We used to expect fathers to simply provide for their children; now we expect a greater commodity than money – time.

But can you really imagine a commencement speech where a high-profile man tells graduating students if they excel, they will inevitably disappoint, and struggle? That if they work and have kids they will be accused of wanting to “have it all”?

No. Yet young women are told this often.

So are mothers, who have long asked for equitable, flexible work practices with reasonable hours, and part time options. Neither men nor women should be discriminated against if they make sacrifices or adjustments for the sake of their families. We should value decisions that put children first.

The problem is not the debate itself; it is a crucial one, and even the experiences of the elite and privileged, in rarified worlds of fortune CEOS or White House advisors is worth examining because they should have clout to make changes, and because, simply, we want women to be able to scale those heights, just as men do.

The problem is the way the debate is framed. Wanting it all? Give me a break.

Or give me large vats of ice-cream and a party full of laughter. I do want that.