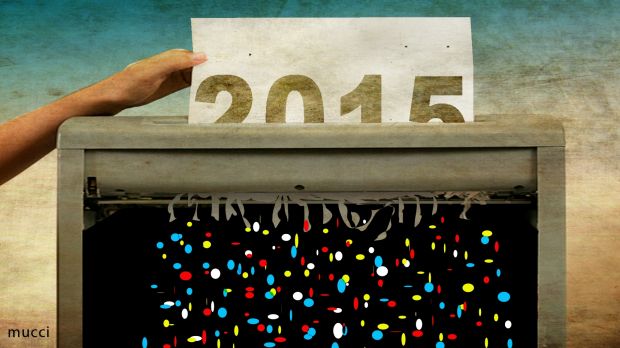

A 40-year-old woman from Wenatchee in Washington State was the first to shove something into the enormous shredder sitting in the middle of Manhattan this week as a watching crowd cheered.

Maureen Dexter said she wanted to publicly destroy a photograph taken of her before she lost 34 kilograms. The feeling of doing so, she said, was “epic”. Behind her in New York’s Times Square, that high-wattage beacon of extravagance and aspiration, a line of people clutched placards, pill bottles, bills and piles of clothes representing their baggage of 2015. It stretched as far as the eye could see down Broadway.

It was New York’s Good Riddance Day – its ninth, though I had never heard of it. I was wandering through the theatre district fretting about not being able to get tickets to the hottest show in town, Hamilton, a ground-breaking hip-hop musical about America’s founding fathers.

When I figured out what the people standing along 46th and 47th streets were doing, I wished I could teleport a bunch of my Australian friends over, give that such an abnormally large number of them said this year has been abysmal: very bad rubbish in need of definitive good riddance. It’s been a mass case of annus horribilis.

Inspiration for Good Riddance day was drawn from the Latin American tradition where at New Year’s, people sew tiny objects into dolls and set them on fire, hoping their pains and frustrations will dissipate in the blaze. (A more lethal, allegedly more merciful approach than stabbing pins into voodoo dolls and hoping for the worst.)

Do we need to burn the past to burnish the future?

The bin vividly reminded me of what a strange holiday New Year’s is: We are meant to celebrate who we were in the past while vowing to be someone else in the future. We vow to be either less hard on ourselves or much harder – a thinner, tauter, cooler, more successful, loved version of ourselves, the person we are truly meant to be.

Singing Auld Lang Syne at the stroke of midnight, we are supposed to be sentimental about the past at the same time we set it on fire.

How can we reconcile this? The Time Square Alliance said any member of the public could come to destroy “any unpleasant, embarrassing and downright forgettable memories from 2015”. And they came, smashing laptops with hammers, slicing up old credit cards, dumping clothes from old relationships and shredding papers with words like “negativity” and “not letting go” on them.

Some were about timeless concerns – “procrastination” and “anxiety”, while others were more contemporary – the Kardashians, Donald Trump and “ghosting” (the sudden unexplained disappearance of a love object from your life and social media, spurred by Charlize Theron’s ghosting of former fiance Sean Penn.)

Some were sad, like a young woman named Stephanie who wanted to eradicate “feeling alone and crying about it”. And others were hopeful; Jennifer from Brooklyn came to shred “everything that kept me from being my truest self,” including an invitation to her cancelled wedding.

New Year’s Eve resolutions seem to divide up into being harder on yourself, and stepping it up, or cutting yourself a break and lightening up. I’m in the lightening-up camp. Not that I don’t have many things to change. I wish I could wake up earlier or entertain effortlessly just once or stop burning the toast or learn how to do hospital corners or care deeply about dust.

But who am I kidding? I just want to place one foot, preferably in a great shoe, in front of the other, love my kids and be a decent person. I asked some of my family what their resolutions were and they came up with “Hang on” and “Stay vertical.” Perhaps this year we should contemplate not achieving goals but shedding idiocy, raising plateaus and casting our gaze to a field far wider than our own fitness plans.

Some at Good Riddance Day pointed to broader societal problems obviously beyond the reach of a shredder. Kelly wanted to bid farewell to “poverty, 2015” and the feeling of being oppressed as a “middle-aged, poor person.” Russian tourist Alyola Shestakova said, rather optimistically, “I am shredding economical and political problems.”

But the greatest uneasiness present in New York is what we worry we can control least: the fear of terror attacks. All week, a great show was made of extra security for New Year’s Eve in Times Square, with plans to screen the predicted one million spectators twice. One commentator called it the most “carefully watched and highly policed quarter mile in the world.” Alongside 6000 NYC cops were 500 officers from the new anti-terror force, the Critical Response Command.

And it’s hard to calm anxiety when none of the US presidential candidates seems to have a clear plan for how to navigate the quagmire in the Middle East. Ted Cruz says he will make the sand of the Middle East “glow” with bombs even as IS enters Jesus’s hometown, Nazareth.

It’s no coincidence that Hamilton is the biggest thing to hit American culture in an eon. It is a show about the birth of American democracy even as the presidential candidates try to compete to say which one can halt, or slow American decline. Celebrating the past, in other words, while vowing to be better in the future. They trumpet that they will make the United States, as Donald Trump would say, “huuuuge” again.

Some would call it delusion, but it’s part of the magic of America; the perennial belief that you can be remade if you will it, that you can burn a past and reinvent a future in one night, that fresh shoots push through all decay.

So what became of the documents shredded in Times Square this week? They were recycled and used as confetti on New Year’s Eve in Times Square. As the crystal ball fell they dropped gently on the heads of revellers – circled by armed police, security staff and trained counter terror operatives – hoping, because we have to hope, that this year, perhaps, might be different.